How watches meet people’s fancy and change their function to become an expression of style

When we ask ourselves today what is the relationship between products and art, we forget that there is an intermediate level that connects them: design. And although this never really took on an identity of its own until the beginning of mass production, there were some highly noble forerunners to it, going all the way back to the practice of wearing a distinctive livery to be recognized – heraldry, widely developed primarily during the Middle Ages – and in the trademarks and signatures of artists and corporations.

Marks, Signatures, and Design

There were several ways that makers used to visually mark objects: trademarks were invented about 2,000 years before Christ in China to distinguish porcelain and vases produced by one kiln or another, and the same procedure was adopted in later eras, where the “Master” craftsmen who were part of a guild were allowed to affix their mark to the objects they made.

In this way, the evolution of craftsmanship went hand in hand with art: since 1500, painters began to affix their signatures to their works to identify them (the first was Michelangelo). And even on watches, the nascent market that was starting to develop imposed the need to certify original watches from imitations. The first watchmaker who created his serial code for numbering watches produced in his laboratory, and marked them with his name, was one of the fathers of English watchmaking, Thomas Tompion (1639 – 1713).

After him, the custom of signing movements became widespread – marking dials came much later, at the beginning of the semi-industrial production of watches. Nevertheless, some watchmakers began to define their style in the conformation of timepieces in a completely autonomous way, and among them, the most famous example was that of Louis Breguet.

The genius of Breguet, the Parisian watchmaker

Abraham Louis Breguet, who worked in Paris around 1800 and came from the school of Lépine, was a true revolutionary, and he did so in three completely different sectors. First, from a technical and mechanical point of view, he was a true innovator who also had an exceptional flair for identifying the most promising developments in the art of watchmaking. In fact, rather than inventing, he spent much time refining the intuitions of others to introduce them into his watches.

Alongside this “technical” side, Breguet was a businessman with a blazing intelligence. One of his most famous designs was the famous “Souscription.” This was an extremely simplified watch, with a single hand indicating five-minute periods on the dial. This timepiece was sold at a promotional price, lower than other Breguet timepieces. In addition, it was available exclusively through a “subscription.” The buyer paid a deposit in advance and the balance when the watch was finished.

Breguet’s third, and in these terms, most interesting contribution to the design aspect was its aesthetic rigor, which soon became a true signature of the House. Almost all Breguet watches produced at the time follow these canons of style, making them as easily distinguishable then as now. Among the many, the presence of a guilloche texture on the dial, which often featured subdials, the signature of the watchmaker painted on the dial, and the famous “secret signature,” an engraved signature that could only be seen in a few special light conditions.

Moreover, the Parisian master’s watches became famous for using a specific variety of hands, the so-called “pomme”: needle-shaped hands, with a thin metal circle towards the end, which thanks to him are now known as Breguet hands.

The 1900s, the century of design

Continuing in history, after Breguet, watch design did not find many heirs in the nineteenth century. It then exploded at the beginning of the twentieth century with the remarkable evolution of wristwatches, which came to the public thanks to the figure of the other great Parisian jeweler and watchmaker Cartier. Right from their origins, the first Cartier watches displayed the famous Roman numerals that would later become an essential part of the Maison’s style and which would proudly camp out on the dials of such seminal pieces as the Santos and the Tank.

And alongside these, other movements, this time artistic, directly influenced the aesthetics of objects and even watches, such as the Bauhaus. The rationalist Bauhaus movement embodied the Central European essentiality of function, stripping objects of useless frills and returning them to their original role. It is to this quest for simplicity and purity that we owe masterpieces such as the Patek Philippe Calatrava, whose first reference, ref 96, with its simple baton indexes distributed around the dial and the second at six o’clock, dates back to 1932.

The passage of watches from the pocket to the wrist allowed Maisons to explore innovative and sometimes daring solutions, not only in the design of the dials but above all in the shapes of the cases, which took on the typical rectangular forms during the Art Deco period, only to return to being round in the following years.

But this veritable explosion of mechanical watchmaking was not accompanied by an equally decisive development of the role of designers, who were often relegated to the shadows of the Maison’s design offices – somewhat as an afterthought – until one of these unchained them and brought their genius back to the limelight.

Gerald Genta and the 1970s

The most famous watch designer of the modern era is undoubtedly Gerald Genta, a true icon of contemporary watchmaking who, in the 1970s, invented not only two of the most famous watches in the world (we are talking about the Audemars Piguet Royal Oak and the Patek Philippe Nautilus), but a truly bustling market: that of luxury sports watches. And along with this, exhuming the figure of the watch designer – an independent profession that without the Italian-born Swiss perhaps would never have been born.

Genta, who initially worked for Universal Geneve, found himself to be the right man in the right place at the right time, and his dazzling intuitions, such as the use of the micro rotor and the formula for luxury sports watches, allowed him to become a star in the firmament of Swiss watchmaking. And after him, who worked for the most important companies, the small boutiques that produced handcrafted watches of extraordinary class and personality, expressing to a large extent the character of their creators, also came back into fashion.

It is to independent watchmakers such as Svend Andersen – creator of animations and astronomical complications – and Vincent Calabrese – the poetic author of the Golden Bridge for Corum – that the profession of independent watch creators was resurrected, and their reorganization into an association that brings them together, the AHCI, Association Horlogere des Createurs Independants, founded in Zurich in 1985 – a statement that qualifies the watchmaking profession, which includes the technical as well as the aesthetic side.

Modern watch design

From the Quartz Crisis onwards, we have witnessed unusual watchmaking mixes, which are still not fully developed. Thanks to the activities of the AHCI and other innovative personalities such as Max Busser, project manager of the Opus series for Harry Winston and now muse of MB&F, the world of watchmaking is substantially changing its perspectives and boundaries, increasingly turning the watch into a plastic palette for experimenting with new solutions.

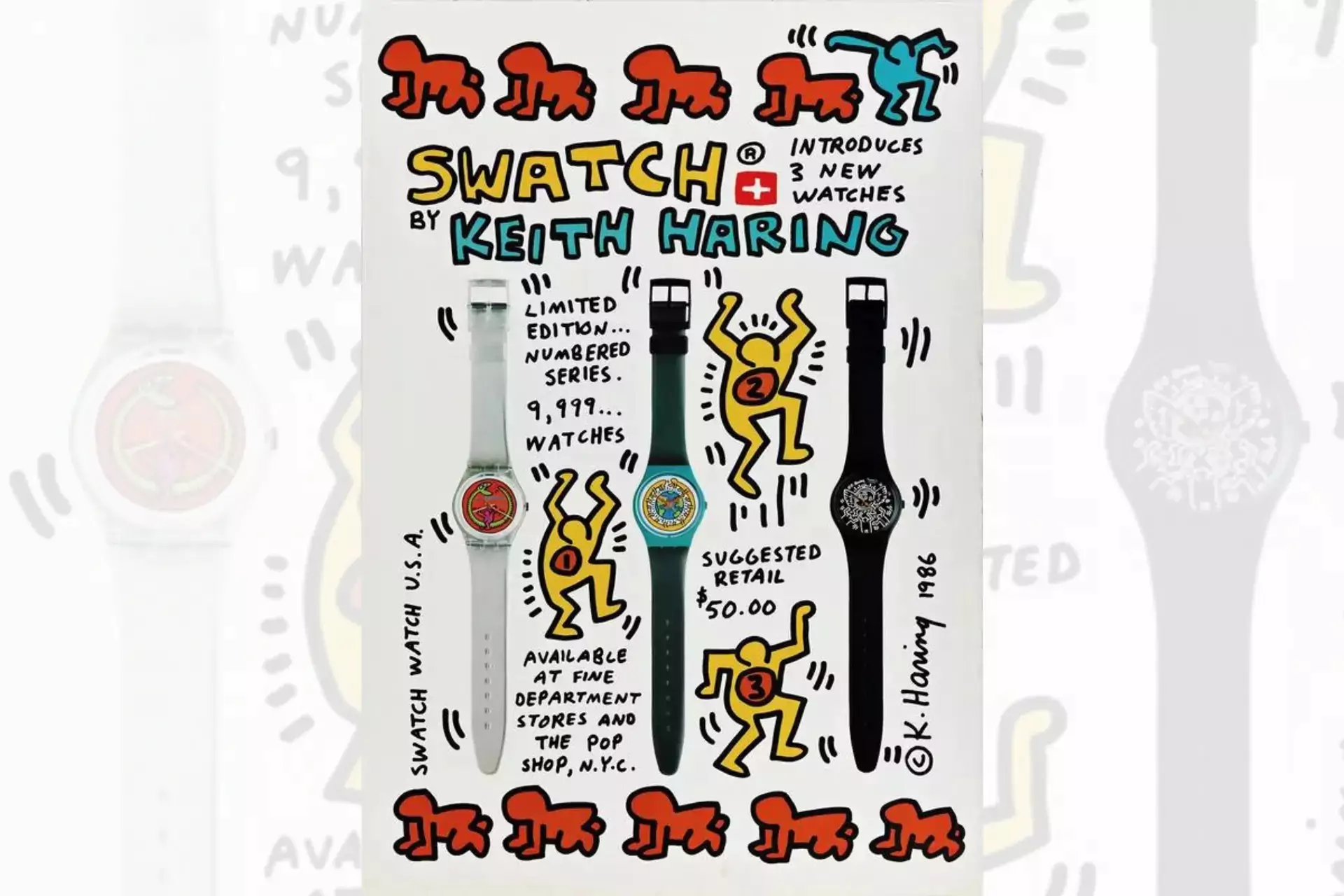

On the other hand, the watch has developed also to turn into a purely fashion object, following the example of the Swatch watches launched in the 1980s, which have become a glittering rainbow of shapes, materials, and colors. A lesson that at a more luxury level has been taken up by Hublot, with its Art of Fusion that makes the watch the protagonist of an infinite number of collaborations, often in Limited Edition, with other players on the luxury scene.

Famous artists, architects, designers then intervened in the Roaring Eighties era onwards. Some obtained noteworthy results, while others just did it for a purely rhetorical exercise (and. well, money), using watches and clocks as a means of expression – but we’ll be commenting only a few, as to examine them all would be enough for a whole book.

We can recall, among the many, the latest constructivist provocations by Alain Silberstein for Louis Erard, the elegant minimalist dial designed by Nendo for Bulgari’s Octo Finissimo, or the Rado Truesquare collection dedicated to modern industrial designers, featuring professionals such as Formafantasma, Yuan Youmin, YOY, and Thurkal and Tagra.